Last week I wrote about Vasilishki where Isidore’s father Shimel was born. Today it is Tiraspol, which is in modern Moldova, because that is where Isidore claimed to be from. Yes, his birth record shows his birth and those of his siblings in Odessa, but the family apparently lived in both Tiraspol and Odessa. We don’t yet have the timeline or why all the children would be born in Odessa, but the family had strong ties to Tiraspol.

At first I was very confused because Odessa is in Ukraine and Tiraspol is in Moldova–two completely different countries. They are only 65 miles apart and when Isidore and his family lived in that region, it was all part of the Russian Empire.

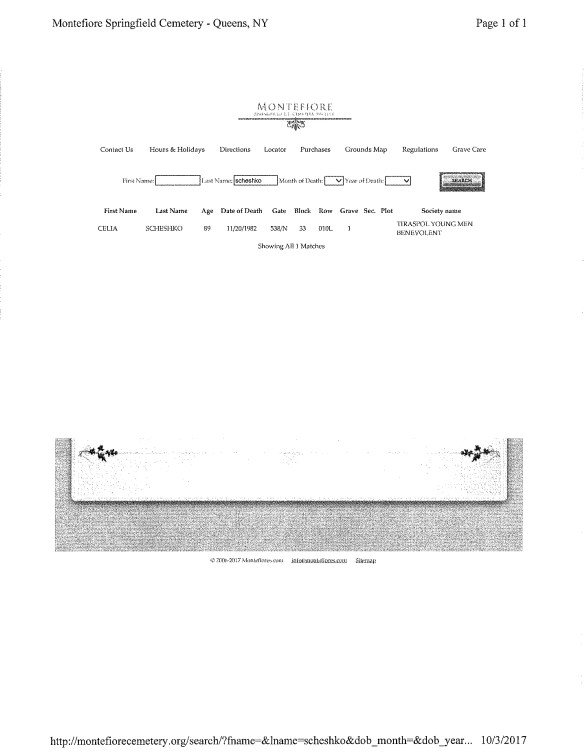

When we discovered the Odessa birth index with the Scheshkos listed, I wondered if Tiraspol had been a mistake, but the cemetery where Isidore and Celia are buried recorded that they were buried by the TIRASPOL YOUNG MEN BENEVOLENT society.

Tiraspol can be spelled Tyraspol or Tirashpol, but should not be confused with Terespol, a town in Poland, near Belarus.

This painting was completed around 1900 by painter Mikhail Larionov. It’s called “A Small Jewish Shop in Tiraspol.”

You can find an old and a new photo of the city here.

Tiraspol is part of the International Jewish Cemetery Project. There are graves there that need protecting or, at least, recording. In 2004, over 70 headstones were vandalized, and the city would not clean up the anti-Semitic graffiti. Here are a couple of photos of the cemetery.

The city is the second largest in Moldova (population about 134,000-200,000, depending on the source). The two state languages in the territory of the Transnistria Republic are Russian and Moldavian, but in Tiraspol, the Moldavian language isn’t used much. You can often hear Ukrainian since a large portion of the population has Ukrainian ancestry, but Russian is the main language.

In the middle ages, Tiraspol was a “buffer zone” (Wikipedia) between the Tatars and the Moldavians, and both ethnic groups lived in the city. The modern city really began, though, with the Russians who conquered the area at the end of the 18th century.

I thought this tidbit from Wikipedia is interesting:

In 1828 the Russian government established a customs house in Tiraspol to try to suppress smuggling. The customs house was subordinated to the chief of the Odessa customs region.

From this and other information I’ve picked up over the past few weeks, I think Tiraspol was part of the greater Odessa area during the Russian Empire years. I do think it’s important to remember that Tiraspol is a city, not a village like Vasilishki.

According to JewishGen, the Jewish population in 1897 was 8,659 and in 1926 it was 6,398. The decline could be from emigration, but there is another story about Tiraspol that needs to be told.

Here is an excellent history from the International Jewish Cemetery Project:

Tiraspol [was] founded in 1795 . . . . On the eastern bank of the Dniester River, Tiraspol is one of the few cities largely unchanged from Soviet Union rule. (Two statues of Lenin still stand.) As result of the political and economic situation that followed the proclamation of the independent (not recognized) Republic of Transnistria, the population of the city in 2004 was 158,069. Tiraspol had a Jewish population since the 17th century. Tiraspol was founded by the Russian general Alexander Suvorov in 1792. In the mid-19th century, Jews from Russia, Dubossari, and Grigoriopol settled in Tiraspol. By 1897, the Jewish community was 27% of 8,668 residents. Nearly the entire Jewish community perished in Nazi concentration camps.

So there it is. What I hadn’t wanted to read. Most of the Jewish community died in the camps. Were the Scheshkos there at the time of WWII? I think it’s possible to come closer to knowing with the following information.

Our researcher Inna’s own family comes from Tiraspol, so she has collected some documents pertaining to the situation right after the Russian Revolution in 1917.

These documents relate to a terrible famine that plagued the area during the 1920s. The majority of people were hungry, but the Jewish population was worse off than the others.

American Jews with ties to Tiraspol tried to help those left behind. The Tiraspoler Landsmanschaft collected donations and sent money for food, such as cocoa, sugar, milk, flour, barley, and fish. But much of it was diverted elsewhere along the way. I read a ONE INCH THICK collection of documents about the dire situation.

Dr. Bacilieri wrote a report in German of his trip to check on the conditions in Tiraspol. He said the chldren were “the worst sufferers and in terrible condition.”

I saw a child about 8-10 years old searching in a dust heap looking for something to eat. I saw another child about 10-12 years old frying the skin of a dog for food. Many children do not return at night but sleep under a fence or on the streets so that they may be in a position to get something to eat.

The doctor says the entire population was filthy and covered with lice. People were sick (often from typhus) and dying, yet their relatives could not afford burials for them.

The Jewish residents of Tiraspol organized a system of men to receive the goods and distribute them. This is how I know that the Scheshkos lived in Tiraspol at this time.

On a Tiraspoler Landsmanschaft memo, Shimen (Shimel) Scheshko is listed as an alternate to the list of men receiving the goods. He and his family were in need.

So the Russian Revolution had not brought about a relief to old sufferings for the inhabitants of Tiraspol. Instead, they had new suffering and many died during this period.

So that decline in population by 1926 could be from emigration, but it could be from starvation and disease.

I was very upset after reading this thick stack of papers documenting the plight of the residents of Tiraspol during this period. And now to discover through the IJCP history that none of the Tiraspol Jews survived the Holocaust, it’s mind-boggling to me. One trauma after another after another.

Here is a little more info from the IJCP about what happened a generation and beyond after the war:

By the 1960s, nearly 1,500 Jews lived in Tiraspol. Police arrested several skinheads suspected of pipe bombing a Tiraspol synagogue in April and June 2002 on 14-15 April 2001. The building was damaged, but the guard was not hurt. 4 May 2004, vandals threw a Molotov cocktail in an attempt to set fire to a Synagogue in Tiraspol. The attack failed when passers-by extinguished the fire. Since 2001, the Welfare Cultural Center combines welfare and cultural programs for the Jewish community. Current Jewish population: 2,300 people in Tiraspol and 130 people in nine surrounding localities. [March 2009] REFERENCE: Jewish Tombstones in Ukraine and Moldova, 551, bibl. 1153, 7/14/1993, GOBERMAN D., title: Image Publishing House, 1993, English/Russian.Source: Daniel Dratwa;. d.dratwa@mjb-jmb.org Jewish Museum of Belgium

I hope that through the IJCP we will eventually find that there are Scheshko headstones in the Tiraspol cemetery. Very few Jewish records exist for Tiraspol, so we were lucky that the Scheshko children and the marriage was recorded in Odessa instead.

There is a site online that I have to mention:

This is a place where all current and former Tiraspol residents interested in their Jewish roots can meet and exchange information about their families.

Click here to go to the site for photos, notable residents, and other information.

Fascinating (and horrible) information, Luanne. I’ll have to go back to look at the links later.

Did you ever see the Polish movie, Ida? A scene of a Jewish cemetery from it flashed into my mind as I was reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have not seen it. Is it an indie or a Hollywood movie or was it a foreign film?

Yeah, it’s incredible info. I couldn’t stop reading the documents on the famine because I had absolutely NO idea.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a foreign film. For some reason, we saw three Polish films that had Holocaust themes in the past year or two. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXhCaVqB0x0

I knew about the famine, but not this area in particular. Then there was another Russian famine in Ukraine and other areas under Stalin in 1932.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It just gets worse and worse. I suppose when I research Odessa and Kiev I will find out more . . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

This post is outstanding Luanne. My ggrandfather Samuel (Shmuel) Haimowitz was born in Odessa and I have read some of the same gruesome accounts of the suffering in the area. I wish I had more time this morning to delve deeper into the links. Your filling my plate with lots on my to do list for later. Again outstanding informative post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh wow, anything from this area then relates to your family as well. And, yes ,the documents said the famine was across Ukraine! Not only were the Scheshkos from Odessa (and Tiraspol), but Celia Goodstein (Isidore’s wife and the gardener’s grandmother) was supposedly from Odessa. I hope we’ll find out for sure.

LikeLike

I can only imagine your horror when you saw Shimen’s name on that list. Dr. Bacilieri’s description of the children is just horrifying—do you know who he was and when he visited? Incredible research, Luanne, and a truly devastating post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I tried to figure out exactly who he was. I think he was Hungarian. And that he had been sent, perhaps by the Landsmanschaft or at least helped orchestrate by them to check on the condition of the Jews in Tiraspol.

So devastating, Amy. When I saw his name, my whole body prickled and chilled.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know that reaction. For me it feels like a solid punch in the gut. And I hold my breath. Thanks for the response about Dr B.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops, to your other question. Dr. Bacilieri visited in March 1922.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear heaven! Sometimes I am simply stunned into silence when I read of these tragic lives – what destiny is this? How do we as human beings turn our backs on such suffering? This adds to your research such gravitas Luanne – it can’t be easy and I am in awe!

LikeLike

I agree, Pauline. It’s absolutely stunning. It almost seems that seeing people undergo such tragedies hardens many people instead of increasing their compassion. So grateful that you’re my friend!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is heartbreaking, Luanne. I admire your persistence in digging through the horrific details to try to piece together the stories of your husband’s ancestors.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s really heartbreaking. I thought I knew “all” the stories since I had saturated myself with Holocaust memoirs (and poetry) for years and presented papers at conferences, etc. But what I knew was really Western European Holocaust history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hugs to you and your husband. Even though it’s heartbreaking, the tales need to be told and preserved. It’s an important work you are engaging in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel as if it is. Sometimes I think I am the only person who thinks so ;), so it’s nice to hear you say it, Amberly! Just got more info last night, too. Sitting on a lot now until after the holidays!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person