Long before the gardener and I ever thought of researching his family history, we would mention the possible etymology or origins of the surname Scheshko (Sheshko). When we were still dating he explained that he had been told it meant sword-maker or metal worker.

Did that turn out to be true or not? And now that we have more surnames, what are their origins?

The expert on Jewish surname etymology is Alexander Beider who was born in Moscow in 1963. According to Wikipedia, “in 1986 he graduated from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology and in 1989 he received a PhD in Applied Mathematics from the same institution. Since 1990, he lives with his family in Paris, France.”

He is a scholar of Yiddish given names and of the history of Yiddish itself, as well as of Jewish surnames. He co-authored the Beider–Morse Phonetic Name Matching Algorithm with Stephen P. Morse.

Wikipedia lists his main works this way:

- Beider, A. 2017. A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Maghreb, Gibraltar, and Malta. New Haven, CN: Avotaynu.

- Beider, A. 2015. Origins of Yiddish Dialects. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Beider, A. 2009. Handbook of Ashkenazic Given Names and Their Variants. Bergenfield, NJ: Avotaynu.

- Beider, A. & Morse, S. P. 2008. Beider–Morse Phonetic Matching: An Alternative to Soundex with Fewer False Hits. Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy 24/2: 12-18.

- Beider, A. 2005. Scientific Approach to Etymology of Surnames. Names: A Journal of Onomastics 53: 79-126.

- Beider, A. 2004. A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Galicia. Bergenfield, NJ: Avotaynu.

- Beider, A. 2001. A Dictionary of Ashkenazic Given Names: Their Origins, Structure, Pronunciation, and Migrations. Bergenfield, NJ: Avotaynu.

- Beider, A. 1996. A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Kingdom of Poland. Teaneck, NJ: Avotaynu.[“Best Judaica Reference Book” award for 1996]

- Beider, A. 1995. Jewish Surnames from Prague (15th-18th centuries). Teaneck, NJ: Avotaynu.

- Beider, A. 1993, 2008. A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire. Teaneck, NJ: Avotaynu.

We are most interested in this last text because it lists Jewish surnames from the Russian Empire.

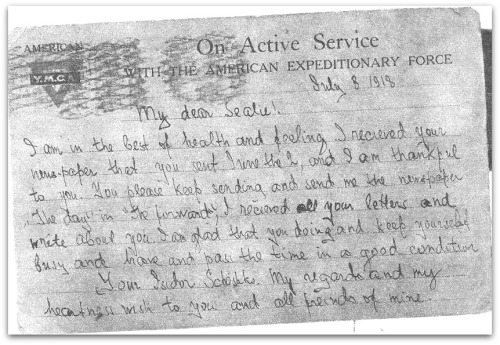

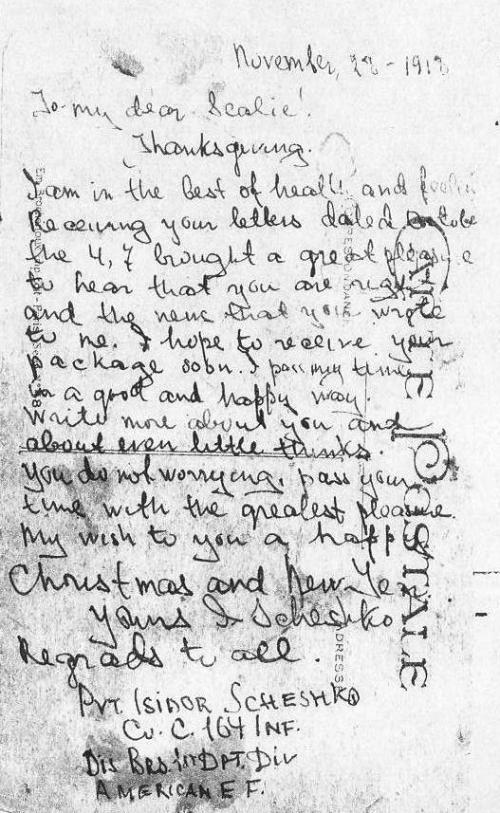

Shimel (Shimen) Scheshko is seated in the center of the photograph. His children are all Scheshkos, of course, and Isidore is standing behind his father.

The mother was born Khaya Brana Pechnik. We learned this from their marriage record.She came from Kupil, which was in the Khmelnitsk province of Western Ukraine. The records in that area that are needed to research Khaya’s family have not survived, but there might be something in the Zhitomir records. Since this is getting closer to the area that the gardener’s mother’s family came from, we will wait and do the search for Khaya’s family at that time as it seems more time-efficient.

We know that Isidore married Celia Goodstein, so we can add that surname to the mix. And now we have information that Celia’s mother’s surname was Suskin. At least that is what Max Goodstein’s death certificate lists as his mother’s maiden name.

This is what Inna reported that Beider wrote about the name Scheshko/Sheshko:

Jews with the Sheshko surname lived in Ukmerge (old name Vilkomir) town that is located in Lithuania, Lida, Belarus, Village Sheshki in Panevėžys district of Lithuania and village Sheshki in Ashmyani district of Belarus. Here are spelling variations of this surname: Shesko, Shesik, Sheshkin(Sheskin, Seskin, Shestkin), Sheshkovich, Sheskovich.

Of course, this means that the name does not mean sword maker or metal worker at all, but is a name derived from a place. On the other hand (because I love to quote Tevye), I asked a Russian friend about it, and she mentioned that there is a type of sword that sounds like Scheshko. It’s called Shashka or Shasqua, and it’s the Cossack sword! When I think of Ukraine, I tend to think Cossacks. What a coincidence . . . . Or not.

Here’s an image from Wikipedia:

Now on to Pechnik. Inna says that according to Beider:

Jews with Pechnik surname lived in Brest, Slonim, and Mogilev. Pechnik in Russian means stove setter. Here are the spelling variations of this surname: Pechnyuk, Pechikov, Pichkar’, Pichkar.

Stoves are metal, so I have to wonder if the idea of the origins of Scheshko came from the name Pechnik. Impossible to know for sure, of course. And it’s still possible, I suppose, that Scheshko has a different meaning.

According to Inna:

According to A. Beider’s Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Russian Empire, Jews with Gutshtejn surname lived in Belostok, Kobrin, Kamenets. The following are spelling variations of the surname: Gutenshtejn; Gitenshhtejn (Gitinshtejn), Gitshtejn (Gidshtejn). The surname means good stone or hat + stone (Utshtejn)

The Americanized form is Goodstein.

Now take a look at the name Suskin. Wow, isn’t that similar to Seskin, which is one of the versions of Scheshko. This is getting pretty confusing, but there could be an explanation for the name beyond Scheshko.

Beider dictionary has no record of Suskin surname. The closest one would be Sushkin. It was found in Polotsk and Mogilev. This toponymic surname traces back to the village of Sushki. Spelling variations are as follows: Asushkin, Sushkovich (Suskovich, Shushkovich), Sushkevich, Ashushkevich.

The spelling variations are maddening, of course. It’s impossible to know for sure, and the point at which these surnames became “affixed” to a particular family would probably be before records for eastern European/Russian Jews would be available so the place of origin for toponymic names would not be helpful except as a point of interest.

For that reason, the only way to track down where these branches came from is through actual records, such as the Odessa birth records that show where Shimel and Khaya came from before winding up in Odessa and Tiraspol.

On another note, I recently discovered that artist Marc Chagall (one of my favorites) was born Moishe Segal in what is now Belarus, from the same region as some of the gardener’s branches. He was born in Liozna in 1887, the same year Isidore was born.

Chagall’s parents